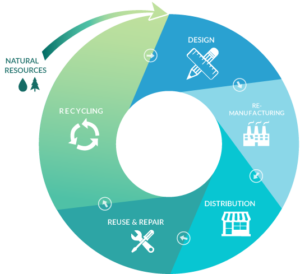

Today, we design both products and packaging to be “disposable”, with little consideration of the true environmental impact or influence on human health. By rethinking the way we consume, and by shifting the responsibility of product management back to the manufacturer, we can begin to address these issues—designing out waste rather than generating it.

For many people, extended producer responsibility (EPR) is exactly the policy approach needed to achieve this, placing increased emphasis on the entire lifecycle of a product and encouraging manufacturers to keep resources in the loop for as long as possible through product stewardship. But what is extended producer responsibility and how does it work? Here we dive in.

What is EPR and how does it work?

Source: Roadrunner

EPR is a strategy designed to identify and encapsulate all the environmental costs associated with the entire lifecycle of consumer products and packaging. The concept was first defined by Swedish academic Thomas Lindhqvist in the 1990s, aiming to work towards an:

“..environmental objective of a decreased total environmental impact of a product, by making the manufacturer of the product responsible for the entire life-cycle of the product and especially for the take-back, recycling and final disposal”

Since that time, the concept has been developed and refined in countries around the world, most commonly taking the form of financial measures that hold manufacturers responsible for the management of waste disposal. This usually means end of life strategies such as:

- Implementing take back and recycling programs for products

- Setting up collection points and recycling pickups for products

- Designing new products that are easier to reuse, repair, and recycle

Underpinning EPR is the idea that manufacturers are better placed to design less wasteful, harmful, and toxic products before they, in fact, become “waste”. EPR attempts to move the burden of waste management away from consumers and government and back into the hands of manufacturers.

All types of products and packaging may be considered good candidates for EPR programs and they can be implemented in various ways. This includes programs put into practice by manufacturers themselves or those that rely on existing recycling infrastructures with financing from manufacturers.

However, EPR still presents a challenge. While the overarching goal is to reduce waste at the source, too often EPR focuses on end-of-life waste management rather than designing waste out of the loop at the source. Below, we look at a few examples of extended producer responsibility and how they might be improved.

Examples of extended producer responsibility

The importance of EPR in a world that is generating more trash every day cannot be understated. In fact, it holds an important role in both circular economy and zero-waste concepts – two of the most forward-thinking waste management systems making an impact today. However, depending on the type of product we are dealing with, EPR programs do not necessarily have to be complex, expensive, or even particularly innovative.

Container take-back programs, for instance, are a simple example of EPR that has been effective in many places. In most cases, consumers will pay a small deposit when products are sold (usually beverages), which is refunded when the packaging waste is returned to the retailer. This places a legal responsibility on the retailer to take back containers for recycling or reuse, and there are currently ten states in the US implementing container deposit laws set out by local government.

However, more comprehensive versions of this system exist in other countries, with containers going back to the manufacturer (or intermediary) to be cleaned and used again. For example, Germany offers two options for recyclable containers; single-use deposit (Einwegpfand) and reusable deposit (Mehrwegpfand). Reusable deposit containers require a much lower initial deposit than single-use, discouraging consumers from purchasing them. Once returned, reusable products are cleaned and refilled by the manufacturer, taking them out of the waste stream to be returned to the retailer to be sold again.

However, more comprehensive versions of this system exist in other countries, with containers going back to the manufacturer (or intermediary) to be cleaned and used again. For example, Germany offers two options for recyclable containers; single-use deposit (Einwegpfand) and reusable deposit (Mehrwegpfand). Reusable deposit containers require a much lower initial deposit than single-use, discouraging consumers from purchasing them. Once returned, reusable products are cleaned and refilled by the manufacturer, taking them out of the waste stream to be returned to the retailer to be sold again.

More complex products, however, require more robust programs, and returning packaging for recycling or reuse is not the be-all and end-all of EPR. The fashion industry is a good example, with certain retailers leading the charge in the move away from fast fashion practices and “disposable” garments.

Patagonia, a longstanding player in the world of sustainable business practice, has introduced initiatives that form one of the most comprehensive EPR programs in the industry. All garments manufactured by the company are guaranteed for durability, reducing the use of virgin resources used to manufacture new products. Trading in old gear for new, free repairs for garments, and a used clothing market all help to promote Patagonia’s commitment to the EPR philosophy and the reduction of waste.

Other garment manufacturers following in Patagonia’s footsteps include MUD Jeans, offering a Lease a Jeans program that allows you to return your jeans after a year for a brand new pair, with all old or damaged garments either being recycled or upcycled into new clothing.

One of the biggest challenges facing extended producer responsibility is in the electronics industry. Take-back schemes for electronic equipment from some of the biggest brand owners in the world are now catching on, and as one of the fasted growing waste streams in the world, more needs to be done in this sector.

One of the biggest challenges facing extended producer responsibility is in the electronics industry. Take-back schemes for electronic equipment from some of the biggest brand owners in the world are now catching on, and as one of the fasted growing waste streams in the world, more needs to be done in this sector.

Dell is widely regarded as the first such manufacturer to implement an EPR program back in 2006, however other high-profile companies such as Apple and Samsung now also operate a variety of programs that allow consumers to return electronics for refurbishment or recycling.

Despite this fact, EPR in relation to consumer electronics needs more support, and organizations such as the Electronics TakeBack Coalition and OECD are pushing for greener designs and more responsible recycling across the entire industry. The end game is more sustainable devices that can easily be repaired, reused, and resold, and the future of our digitally connected world depends on more.

EPR and Sustainability in the US

While EPR systems in the European Union may typically be ahead of the curve, there is now increased interest in the US, with dozens of bills currently making headway towards a more comprehensive approach.

Recent movements within the packaging industry, for example, have seen a range of influences including pressure from lawmakers, the rising cost of recycling, and growing public concern regarding plastic packaging and plastic waste push for better EPR systems.

This increased momentum is empowering producer responsibility organizations, such as the Packaging Network, to introduce more robust and comprehensive EPR legislation that prioritizes environmental protection.

Currently, the following states have bills that aim to improve recycling rates, offer incentives for more sustainable product design, advocate the use of stewardship programs, or simply ban certain packaging products from being sold unless they are able to comply with strict guidelines.

- California SB 54

- Hawaii HB 1316

- Maryland HB 36

- Massachusetts HD1553

- New York S1185

- Oregon HB 2592

- Washington SB 5022

In addition to these, the following states are expected to introduce EPR legislation in the future:

- Colorado

- New Hampshire

- Vermont

- Maine

In addition to legislation covering packaging, there are currently 19 states that implement a range of different EPR laws—covering everything from batteries and e-waste to pharmaceuticals. It is hoped, as these laws gain traction and effectively reduce waste, more EPR legislation will be implemented to combat an even broader range of products and packaging materials.

Extended producer responsibility and the future of waste management

There can be little point denying that we produce too much waste. Recycling levels in the United States usually max out at around 40%, and most of that figure represents products that are, relatively speaking, easy to process into new materials. EPR is an opportunity to increase that figure while simultaneously reducing the burden on municipal and private sector recycling facilities.

There are, however, a number of challenges to address as EPR policies and regulatory initiatives develop. These include:

Overlapping roles and responsibilities

- EPR programs sometimes hit problems when trying to identify exactly who should be responsible for the waste. For example, while a retailer may sell products and provide collection stations for waste, they generally do not manufacture them. Additionally, a brand owner may only be responsible for manufacturing part of any given product, leading to questions over who takes care of the waste.

Free riding

- Particularly in the case of online retailers, free riding can be an issue when responsibility is in question. Since ecommerce is rising fast, and with no centralized brick and mortar stores to collect waste, many products end up with other EPR stakeholders taking responsibility—or not.

Lack of enforcement

- Enforcing any part of EPR policy is difficult. For example, both global authorities and local municipalities need to monitor and control EPR programs across a broad range of industries. If issues arise, through illegal landfilling or free riding, for example, clear legal responsibilities need to be identified through EPR law, with all governmental stakeholders able to fine or rescind licenses of those responsible.

Economic issues

- The economic issues surrounding EPR programs are difficult to ascertain. To begin with, a lack of transparency from both manufacturers and waste management partners can lead to difficulties in identifying the full cost of recovery and subsequent effectiveness of EPR programs. However, as investors begin to recognize the importance of the environmental, social, and governance (ESG) policies of companies, these issues may take a more prominent role in how EPR is prioritized.

What is clear is that many of these challenges can be addressed by placing a higher value on what we now identify as waste. For example, e-waste is considered both highly valuable, thanks to the precious metals used within the construction of PCB boards and other components, and also highly toxic when disposed of in landfill. By placing increased emphasis on the environmental costs associated with allowing products to go to waste, we may begin to meet the challenges facing EPR today.

Finally, with EPR still in its infancy, the development of more modular technologies and products that are easier to recycle should allow more efficient and cost-effective systems to be implemented. The future for EPR lies in its ability to provide legislators with the tools they need to reduce the environmental impacts of individual manufacturers, placing renewed emphasis on reducing solid waste at the source rather than dealing with it at end-of-life.

To learn more about EPR and other issues facing the waste management industry, subscribe to our blog, or speak with one of our TRUE Waste Advisors.